Chapter 13 MARBLE PALACE |

The building erected in 1768-1785 by A.Rinaldi is unusually richly decorated with stone both in the exterior and interior. Up to the present it is a model of the fine art of combination of rocks of different colours together with employment of various techniques of stone surface finishing. This manner of decoration had permitted the architect to create the palace that is stately and light, monumental and elegant at the same time. The discussed creation of stone is not a single work by A.Rinaldi through which he had become a fairly well known. Before proceeding to the design of facades of the Marble Palace with natural stone, that is rather costly material precluding any mistake when it is in use, the architect improved his skill, putting up mile-posts along the old Peterhof and Tsarskoe Selo roads, building the Chesma, Marine and Crimean columns and constructing the Kagul obelisk and the Eagle column in Gatchina. In the course of the work he mastered his technique, step by step finding solutions and testing their validity.It is pertinent to note that demands imposed upon the project were particulary artistic and means assigned for the construction were colossal because the palace was built to the order of the Empress Catherine II herself for her favourite and devoted helper – Count G.G.Orlov, as “an edifice of gratitude”. It is appropriate at this point to juxtapose some figures. G.G.Orlov had made Catherine II a present in return for the Palace. It was one of the largest faceted diamond known the world over at that time. The precious stone weighed as much as 189.62 carats (37.9 g), it was set in the tsarist sceptre later and took its name “Orlov”. But as Grigory Orlov died before the completion of the building, Catherine II bought the palace back for the imperial family in 1783. Orlov’s heirs had received 1 500 000 roubles. The total cost of the building amounted to 1 463 613 roubles, while the diamond “Orlov” was valued at 2 399 410 roubles late in the XIX-th century. For the construction of the Marble Palace special search for marbles and “agates” were undertaken over the Urals and other regions of Russia. Marble was brought to the building site from stone quarries discovered on Ladoga Lake shores, in Karelia and Eastland just at that time. “Wild stone”, as granite was then called, arrived from Finland. White and coloured marble was carried from Italy, white marble of highest quality used for sculpture works was delivered from islands of the Greek archipelago. Some part of the marble was conveyed from the Office of Isaac’s Cathedral buildings. A hundred of men worked at finishing the stones every day. Antonio Rinaldi used natural stone in such a way that its colour and facture were in harmony with architectural forms of the Palace. Moreover, investigators of the architect’s creations note in addition other peculiarities of the edifice. For example, as D.A.Kyuchariantz put it, erecting the palace, Rinaldi tried also to attain “harmonic unity of the building appearance with northern nature – with greyish smooth surface of the Neva water and delicate, soft colours of the pale sky”.* * Kyuchariantz D.A. An-tonio Rinaldi. Leningrad, 1976, p.34. The lower floor of the Marble Palace is faced with pink Vyborg rapakivi-granite. Special technique of finishing of the stone was used there. It was so called “nakovka” (forging on or over something) that was cutting of narrow parallel furrows on the stone surface. In the result of it the rock became rugged and its colour intensified up to dark-pink.

The southern facade of the Marble Palace. Pink rapakivi-granite and grey Serdobol Granite serve as a background for lighter Tivdiya Marble used for the pilasters, frieze and parapet of the roof. The monumental ground floor serves as a basement for the more light-coloured upper part of the palace, two floors of which are united by pilasters and columns of Corinthian order. Walls of the first and second storeys are faced with grey Serdobol Granite. The architrave, upper cornice and outside win-dow-frames of the ground floor are made of the same rock. Outside window-frames of the first and second storeys are cut out of light-grey Ruskeal Marble. The pilasters and columns are hewn of rosy Tivdiya Marble and their capitals and bases are carved of a white Uralian one, quarried in the vicinity of the Polevskaya dacha (country house). Garlands placed above the windows of the first floor are carved of the same marble. Slab-panels, on which the garlands are fixed are made of Juven Marble brought from the island Joensuu situated near Serdobol. Being coloured grey-to-black, Juven Marble exibits distinct banded texture clearly seen from a distance. The frieze and high attic of the edifice are also faced with rosy Tivdiya Marble.

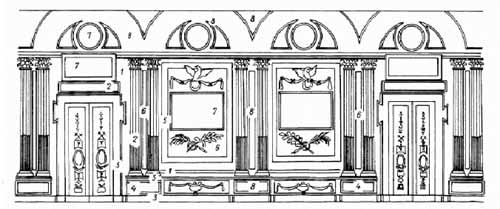

Coloured stone in the interior of the Marble Hall in the Marble Palace. The drawing by N.B.Abakumova. 1 - grey and yellowish-grey Uralian marble; 2 - pink Tivdiya Marble; 3 cherry Tivdiya Marble; 4 - green Levanto Marble; 5 - yellow Italian Marble; 6 - lazurite; 7 white statuary marble; 8 - stucco (artificial marble). Set up on the roof of the Marble Palace were vases of light-grey Revelsky dolomitic Marble. Carved of white Italian Marble quarried from deposits of Serravezza were cartouches on the northern and southern facades, a vase on the clock-tower, and two figures standing on each side of the tower. The same rock was used for vases and compositions of armour installed on pillars of the garden railing. The inner decoration of the palace was carried out in stone as well. Unfortunately it was almost entirely destroyed during the time when the Museum of V.I.Lenin was housed in the building. Only the interiors of the Grand Staircase and Marble Hall still survive. With the exception of some small sections, the Grand Staircase from the ground to the second floors is entirely lined with natural stone. Its steps are made of dark-green, almost black, Brusna Sandstone. The banisters and balustrade, pilasters and columns of the Staircase, as well as niches for sculptures are made of grey, patterned marble. In spite of the generally grey colour, this marble is extremely diverse in its pattern: in some places the stone is grey, unicoloured, while in others it demonstrates alternately spots and veinlets of purely white calcite, or of black carbonaceous matter and sharp banding with interlayers crumpled in irregular, as if ruffled, folds. It should be mentioned that the colour and pattern of the marble depend, to a large measure, on a direction of sawing up of stone blocks. The sawing along the banding plane of a marble block results in an unicoloured stone with a blurred, vague pattern, at the same time sawing across the banding reveals the streaky, ribboned structure. The design of the marble is best seen in the round columns and in large slabs with intricate profiles that line niches on the staircase landings. Previously statues of white marble carved by Fedot Shubin were standing in those niches. Survived still today is the round medallion with the bas-relief portrait of Antonio Rinaldi hanging on the wall of the vestibule, oposite the entrance. Upstairs thin branching black veinlets and spots appear in places in the grey marble. The marble around them gets rusty-yellow hue. The black matter that makes up these spots and veinlets is represented by chlorite. It is a mineral containing iron. Oxidation of this element gives the marble yellow and brown colours. In places, where the spots are abundant, the grey marble turns into yellowish-grey one, that is more decorative. Made of the yellowish-grey marble are massive outside window-frames in window niches on staircase landings. This marble shows vaguely banded pattern and could be taken for some specific type of marble if the above-mentioned change from the grey stone to the yellowish-grey rock was not clearly traced. To the careful observer, the evidence of identity of the grey and yellowish-grey varieties of the marble may be seen in their coarse-grained structure (grain size ranges from 2 to 7 mm), in the shape of calcite grains and in the degree of their transparency. The rock is translucent at several millimetres downward. V.G.Pudovkin, an experienced expert in facing stone working in the Geological Institute of the Karelian Branch of the Russian Academy of Science, considers the marble facing the Grand Staircase had been brought from the Urals. Just by that time, indeed, the marbles of the Polevskaya Dacha, Marble Factory and other deposits in the neighbourhood of Ekaterinburg (Catherinesburg) that became famous later had come into development. The grandeur of the staircase is accentuated by rich fretted cases of doors leading to the private appartments of the palace. As the material for them served the same banded black-white Juven Marble that was used for the panels established on the facades of the building. Rather thick zigzag black and greyish-white layers in this marble have sharp contacts and are clearly defined. Stone-cutters hewed out the door-cases intricate in their design and profile. It was done in such a way that bands have generally vertical orientation, therefore the stone decoration produces the impression of the aspiration upward. The effect of the just proportion, harmony and elegance in the refinement of the Grand Staircase had been accomplished by those means. Garlands above the doors, rosettes of the capitals and bases of the columns are cut out of white marble. Most likely it is the same rock that was used for the analogous garlands fixed on the facades of the palace. Among other apartments of the Marble Palace the Marble Hall produces much more profouned impression. Today it is a hall with two rows of windows, but at Rinaldi’s time windows were located only on one its side. Walls of the hall through the height of the lower storey are lined with natural stone of different colours, adorned with gilded bronze and embellished with bas-relief panels performed of white marble. Rather common in the literature on the Marble Palace is the assertion that no less than 12 kinds of marble had been used for the decoration of the Marble Hall. Under close examination of the hall this figure may be reduced to 7 with allowance made for rocks of other types. It should be pointed out that typical of any coloured marble is a wide variety of different patterns and shades. That is the reason, why the interior of the Marble Hall seems to be decorated with a larger number of varied kinds of marble. The arrangement of the different types of the coloured stone in the decor of the Marble Hall is illustrated schematically by a drawing at p.130. Below is given the brief description of these types.

Rapakivi-granite and Carrarian Marble in the railing of the Marble Palace. Grey and yellowish-grey coarse-grained Uralian Marble identical with that used for the Grand Staircase decoration is of minor importance in the Marble Hall. The rock serves as the background for other marbles and is used rather miserably: in the piers between pilasters, near the doors, as frames of panels made of brightly coloured marbles. In some places in the grey and yellowish-grey marble fine concentric banding of grey and brown-yellow colours is observed. Its pattern resembles a cut of a tree’s trunk. The marble of such a type was quarried at the Fominsk deposit and sometimes it is used for decoration of modern buildings. Pale-rosy, of very delicate shade, in places with dark-red veinlets Tivdiya Marble is applied for pair-pilasters covered with cannelures and standing along all the walls, for frames of panels cut of white marble and fixed above the doors, and for lining of the window niches. Cherry with white and rosy veinlets Tivdiya Marble, often very dark, was used for decoration of the lower part of the walls. The wide plinth along the perimeter of the floor under the pilasters are performed of the same rock. Green serpentine Italian Marble with white calcite veinlets represents almost a breccia. Such a marble was called Verde Antico (Green Antique) and most likely was brought from stone quarries existing in the proximity of the Italian town Levanto, hence is its second name -Verde di Levanto (Green Levantian). Cut out of this rock are slab-panels under the pilasters. Italian Marble of rich golden-yellow colour with sparse black and brown zigzag thin veinlets is used for door-cases equally intricate in their architectural design to ones of the Grand Staircase. The same rock is seen in window-frames, as well as in framing of blue lazurite panels. It is extremely fine-grained, dense, quite opaque, but bright and decorative marble. Yellow colour of the stone harmonizes excellently with gilded bronze of the capitals and huge crystalline lustres, so that at a glance the Marble Hall looks like a golden state-room. Lazurite quarried on banks of the Slyudyanka river in the South-Baikal area was used for the decoration of the hall in insignificate amounts. This stone would be more properly named as lapis-lazuli, or lazuritic rock consisting of light, or leucocratic minerals such as calcite and others among which not large phenocrysts of rich blue lazurite are scattered. By and large the rock is spotty light-blue. Narrow vertical insets between pilasters and enormous panels bearing bas-relieves of white marble are gathered of separate pieces of this rock by the method of “Russian mosaic”. Lapislazuli representing the most expensive stone in the hall decoration is the worthy background for the valuable marble bas-relives while the panels of lazurite is framed by golden-yellow Italian Marble. White statue marble imported from Greece was used for sculpture. The remarkable Russian sculptors M.I.Kozlovsky, F.I.Shubin and Italian statuary A.Valli had carved both bas-relieves arranged on the walls of the Marble Hall and sculptural ornaments: branches with leaves and flowers, eagles keeping garlands and vases in their claws. The stone decoration of the Marble Hall strikes not only by its many-coloured appearance, spruceness and richness, but first and foremost also by the mastery of execution of the works, perfection of rock finishing and taste, beauty and proportionality in matching of stones chosen with extreme precision and delicacy. The most expensive and rich in colour stones accentuate the main details of the interior – pilasters, windows doors, and frames for bas-relieves. Uniform neutral grey stones serve as the background. The upper tier of the hall that appeared at the reconstruction of the Marble Palace in the middle of the previous century was made of artificial marble. It is interesting to note that performed just of the false marble imitating lazurite was the narrow panel between the pilasters standing in the central part of the western wall of the Marble Hall and separating the two bas-relieves by M.Kozlovsky; of the artificial marble painted as if it is natural serpentinite the dark-green slab lying under those pilasters had been made. Identical with this slab are panels of artificial marble the opposite wall bears in its central part. Artificial Marble, or stucco (the Italian for plaster or parget) was produced of finely grated gypsum with addition of gum and pigment-paints. That gypsum mass was put on a wall and after its solidification a master began to scratch thin furrows and small holes on the surface that were filled with additional pigments for imitation of veinlets and inclusions characteristic of natural stone. Later on, all the surface was polished with pumice and tripoli (diatomite) and the final lustre was glazed with stems of horse-tail. With that artificial marble big panels of walls, columns, pilasters were covered. Stucco resembles natural marble, but differs from the latter in its lustre and seems to be warmer by touch. Among stone decorations of other premises of the Marble Palace eight perfectly polished columns of grey Serdobol Granite standing in the oval passage room survived until the present time. There is evidence that in addition to marble and lapis-lazuli appartments of the palace were adorned with jasper as well. However the fate of the jasper adornments is unknown. A small-sized fountain placed in a garden in front of the main entrance to the palace is noteworthy. The water here drops on pieces of porous tuff. The rock is one of varieties of Pudost Limestone formed at deposition of calcite from water solutions. Such a porous tuff was applied widely by Petersburg’s architects of the XVIII-th century for construction of grottos, fountains and garden pavilions or summer-houses in gardens and parks. The Marble Palace was rebuilt in the 40-50-s of the previous century by a group of architects under the supervision of A.P.Briullov and Rinaldi’s interiors were considerably transformed at that time. After the revolution some changes of the inner design of the palace took place. They were made in relation to housing in the palace of the Leningrad Branch of the Central Museum of V.I.Lenin that was opened in 1947. For the years elapsed after the time A.Rinaldi had finished the building of the Marble Palace, the superb marbles of the facades polished to a glassy lustre and other magnificent natural stones used for the facing have lost their former splendour. It was just the marble that has particularly suffered. Being a very unstable material, marble loses the gloss easy and transforms gradually to gypsum under the action of sulphurous gas contained in the air. The facades of the palace were repaired in the 1950-s. Restored at the same time were carved details, capitals and garlands of white marble gone to ruin. They were anew cut out of white marble and coloured with strong tea to match the extant stones. Cracks in the natural stones were first filled with a specially matched mastic and then all columns, pilasters, capitals, frames, cases and other detailes of marble were polished again to a glassy lustre. A number of marble vases adorning the attic proved to be extensively damaged and crumbled into small pieces. Some of them, most likely rather long ago, had been replaced by rude concrete mouldings. By good fortune, fragments of the broken vases had been retrieved on the attics and specialists managed to gather several vases from them. Three vases were newly cut from the same Revel dolomitic Marble. The granite was also cleaned of dust and soot and covered with “nakovka” again at the places where it had been lost. In the 1970-s the works on restoration of some interiors of the Marble Palace were accomplished. In the Marble Hall cleaned of dust and washed were sculptural ornaments. Cracks and hollows in the marble facing were simultaneously filled with mastic. Subsequently everything was polished up to a high lustre. Later the restoration works were performed for the Grand Staircase. By that time, 20 years elapsed after the restoration of the 1950-s, the marble facing of the palace began to break down. The fillings of mastic became chipping and marble got dull again. In 1975 the second restoration of the outer walls of the palace got under way. It was conducted with the application of materials for filling of hollows and cracks that were resistant to the influence of the atmosphere. However, up to the present, there has been no matter discovered to withstand fully the harmful action of the atmosphere on marble and therefore the marbles of the palace facades continue step by step to lose the gloss and to cover with a thin earthy coating of gypsum. Late in the 1980-s the walls were repaired once again, but due to the poor quality of the gloss, they are doomed to rapid soiling and weathering. In 1996 the equestrian statue of Alexander III was put in the cour d’honneur (open court yard) of the palace on the pedestal from under the armoured car of Ilyich (Lenin). Until 1937 it was standing on the huge granitic base in front of the Moscow Railway Station and later was taken away and kept in the court of the Russian Museum. The story of the quarrying of the granitic monoliths and their disappearance after 1937 can be found in our books published in 1993 and 1999. Several blocks sawn of those monoliths had been used for the construction of the pedestal of the monument to N.A.Rimsky-Korsakov installed near the Conservatoire. |

To the beginning |