Chapter 3 COMPOSITION AND PROPERTIES OF STONE |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

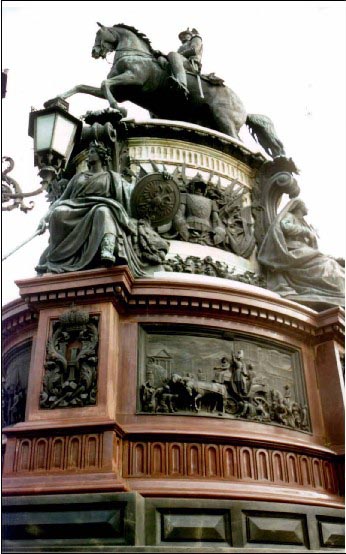

1. GranitesGranite ranks among the most generally employed building, decorative and facing materials since antiquity. The rock is strong, resistant and relatively workable, easy-to-machine for the forming of articles of different shape. It holds a polish well, and weathers very slowly. Usually granite has a clear granular homogeneous texture and is generally pink or grey, in spite of various colours of grains of different minerals composing the rock. Rather commonly granite makes up high cliffs easily accessible for the working of an open-cut quarry. It also occurs as boulders, blocks and coarse gravel. All these peculiarities of composition, colour and occurrence of the stone have long been known, but at times they are inadequate to distinguish granite from other rocks, such as syenites, diorites, granodiorites and some gneisses. Rocks of a number of different types were used in St.Petersburg under the name “granite”.A specialist-geologist determines granite as a crystalline rock originating at depth in the course of magma solidification or during another process. They consist of three essential minerals: feldspar (usually its content is about 30-50 vol %, quartz (approximately 30-40%) and mica (up to 10-15%). As noted above, granites from different deposits had been used in the building of the centre of St.Petersburg. They are pink granites: rapakivi, Gangut, Valaam (from Herman Island), from Antrea and grey granites: Serdobol, from Antrea, Nystadt, from Kovantsaari. All of them show characteristic qualities of colour, granularity, pattern visible to the naked eye and depending on their mineralogical composition and texture. Rapakivi – granite Cut from this granite is the well known Alexander Column, and constructed of blocks of the rock is the monument to those who had fallen in the struggle during the Civil War, February and October revolutions (the monument had been erected in the middle of the Field of Mars). Standing on a monolith of rapakivi-granite is the “Bronze Horseman”; cut from the same rock are columns of St.Isaac’s Cathedral, pedestals of sculptures put up in the garden at the Admiralty and of the monument to Nicholas I in St.Isaac’s Square, portals of buildings of the Morskoy Equipage (Naval Crew) at the Moika River, figures of lying lions in front of Laval’s house on English embankment. Basements of buildings of the Admiralty, General Staff, Senate and Synod, and the ground floor of the Marble Palace are faced with rapakivi-granite. Blocks of the latter form the Prachechny (Laundry) Bridge across the Fontanka River, as well as other old arched bridges. The stone is also frequently seen among slabs of pavements and in parapets of embankments. Finally, a seldom for our days case: the rock was used for consoles supporting balconies of some old houses, such as N 30 on the Dvortsovaya (Palace) Embankment, N 4 on the English Embankment, N 13 on Nevsky Prospekt. The list of examples of use of rapakivi-granite could be continued further. All rapakivi-granites used in the building of St.Petersburg were quarried from the big so-called Vyborg massif. At present it has been found that the massif occupies an area of about 18 000 km2. Today there are also the Salmi (Lake Ladoga area) and Korosten (Ukraine) massifs, but in the past granites from them were not used. In days of yore, granite of the Vyborg massif was worked from several quarries in the vicinity of the Finnish town Fredrikshamn (Hamina). The best known granite quarries are the Piterlaks (Piuterlahti) and Gimmekyul. The Piuterlahti both private and state stone-pits were located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and one of them presented an islet entirely composed of rapakivi-granite. Stone for the Alexander Column and Isaac’s Cathedral was obtained from those famous quarries.

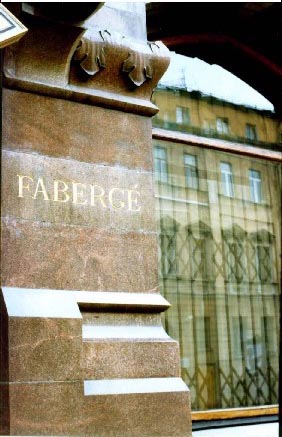

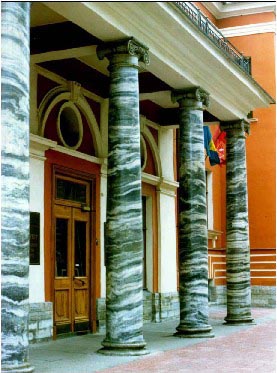

Rapakivi-granite. The rock can be seen everywhere in St.Petersburg what is the city's characteristic feature of a sort. Depending on a place of production, rapakivi-granite was called either Finnish, Sea-stone, or Vyborg, Piterlaks, while in accordance with its colour and wide application, the rock is often spoken of as, ordinary pink or red granite. When viewed closely, the stone readily reveals its grains. A texture of the rock is remarkable too. It consists of large (to 5 cm) round or oval, inclusions of pink orthoclase feldspar, surrounded by white rims of another feldspar – oligoclase. These ovoid segregations or inclusions pack the rock and are bonded by a medium-grained groundmass consisting of pink and white feldspars, grey and black quartz, green-black both mica and hornblende. The pattern of the rock is best seen in wellpolished surfaces, such as the columns of St.Isaac’s Cathedral. Rapakivi-granite structure is easily observable at the lion figures in front of Laval’s house, but signs of weathering are clearly pronounced here. Complex shapes of the sculptures seem to stimulate the destruction, disintegration of the rock. It should be noted that the Finnish word “rapakivi” means “rotten (crumbled) stone”, the term reflecting a rapid weathering characteristic of the rock. Usually at the surface and to a depth of approximately 1 m (even deeper in places) rapakivi-granite is fractured, partially replaced with argilaceous minerals, unstable, not solid and therefore it is unfit for building works. Small boulders of this granite lying on the ground, or in soil crumble away into separate pieces and grains easily. However, being mined at depth and cleaned of an exterior weathered masses, rapakivi-granite is solid and stable when used in objects having simple shapes and smooth surfaces. But its rigidity does not compare with the durability of fine-grained granites which hardly weather. The Sphinxes put up on the University Embankment in front of the Academy of Arts had been carved in Thebes of a granite of such a type about 3500 years ago and they have survived almost perfectly. Sometimes Finnish rapakivi-granite differs in appearance from typical varieties. Thus columns of a classical portal of the house at N 7 in Pochtamtskaya (Post Office) Street are also hewn from rapakivi-granite, but the stone is evenly grey rather than pink. The structure and mineralogical composition of the rock are the same as that of ordinary pink granite, while the colour is quite different. Another example of the use of grey rapakivi-granite is following: the plinth of the General Staff from the side of the Palace Square, to the left from the Triumphal Arch is faced with slabs of pink rapakivi, but to the right, only grey slabs of the same stone were applied. And in places – especially in the thoroughfare under the Arch, both grey and pink granites come together. We call the readers’ attention to these facts, as grey rapakivi-granites have not been mentioned in any description of the city and they are really few and far between. Gangut Granite This Finnish granite came into use in the building of St.Petersburg late in the XIX-th -early in the XX-th centuries. Constructed of that rock were abutments, waters cutand piers of the Liteiny (Foundry) Bridge. It was used in the revetment of the building of the former insurance company “Russia” erected in Bolshaya Morskaya (Great Naval) Street and for the facing of the Buddhist Temple on the Primorsky (Seaside) Prospekt. The facade of the former shop of Faberge in Great Naval Street was richly decorated with the same granite. In common with all Finnish granites Gangut one is rather workable and holds polish perfectly. It was transported in the city by the joint-stock company “Granite” from quarries of a small island lying near the cape Gangut (Hanko), South-West Finland. The granite has a deep even red colour. It seems to be alternately homogeneous or banded in rusticated masonry, cornices and other architectural elements. The thin winding, flexuous bands of black tiny flakes of biotite in a fine-grained groundmass of pink feldspars and grey quartz are most pronounced at columns and slabs of the socle of the jewelry shop “Jakhont” (“Ruby”, “Sapphire” – the former Faberge House), the textural peculiarity making the granite look like a gneiss. Valaam GraniteThis old name is incorrect, regarding a proper geographical nomenclature. It is assigned to gneissoid granites from stone pits situated on an island another than Valaam that lies near the northern shore of Lake Ladoga. The island bears the name Syyskuunsaari and the quarry is called Ladozhskaya. In olden days, when the Valaam Monastery possessed those lands, the islet was referred to as St.Herman’s Island and the stone quarry was spoken of as either Valaam, or Herman’s one. Sometimes it was called the pit of the Church’s Bay after St.Alexander Nevsky Church, ruins of which are yet standing here. In the centre of our city, stone from the Valaam

Pink gneissoid granite delivered from the Gangut Peninsula and Syyskuujansaari islands. quarries was applied in the facing of the house at N 40 erected in Great Naval Street. In other districts it is used for the revetment of piers of the Trinity Bridge and can be seen among facing blocks of the former Tsar’s Pavilion at the Vitebsk Railway Station and of the building of a food shop on Zagorodny (Suburban) Prospekt. In Kronstadt, this stone found use in the construction of the former Tsar’s Landing-stage. Typical features of Valaam granite are best seen in facing slabs of the house N 40 in Great Naval Street. The colour of the rock changes from light-pink to dark-pink and red, the texture being heterogeneous – banded and fluidal, that is, gneissoid. Usually, the bulk of areas of facing slabs consists of fine-grained homogeneous aggregate of microcline, oligoclase and quartz alternating with indistinct medium-grained bands of the same composition and with thin well defined interlayers enriched in black flakes of biotite. The rock banding is flexuous, the pattern being cut with veinlets of medium-grained microcline. All these pecularities suggest the rock to represent a special variety of granites, that is granite-gneiss. Owing to the unfortunate name, the Valaam granite can be mistakenly identified with another granite that was also quarried by the Valaam Monastery in the past. However this rock occurs elsewhere – on St.Sergius’ Island (or Puutsaari, Puutsalo) located not far from the north-western shore of Lake Ladoga. Red granite from that deposit had been used for the pedestal of the monument to Catherine II on Nevsky Prospekt. The stone differs markedly from the Valaam Granite. Antrea Granite Antrea Granite appeared on building sites of our city from the end of the XIX-th century. It was available from the Finnish Company Vaynio from quarries situated along the Vuoksa River, near today’s Kamennogorsk (Stone Mountain Town). Pink variety of that granite was used for the casino of the Hotel Astoria. Carved of the same granite, but a grey one, is the monument to the Kuindji artist put up at the Smolenskoye Cemetery. It can be seen in the rusticated masonry of two lower floors of the Hotel Astoria that the granite is dense, massive and homogeneous. Usually it has medium- or fine-grained texture and contains microcline inclusions of size 2-4 mm here and there. Depending on the content of pink microcline and black minerals, such as amphibole hornblende and biotite, the rock colour changes from light-pink to light-grey. Kovantsaari Granite This Finnish granite was brought to the city from ourcrops found on the Vuoksa River. The rock of the deposit Kovantsaari, but obtained from modern quarries at the railway station Vozrozhdeniye can be seen in the Grand Platform Hall of the Moscow Railway Station, the floor of which is paved with pink slabs of the granite. It consists of small prisms of pink microcline in a groundmass of grey quartz and melanocratic dark minerals. As the microcline is oriented in parallel, the texture of the rock is fluidal. There are rare large inclusions of pink microcline (the size ranges from 3-4 cm to 8 cm).

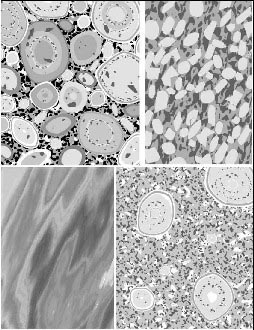

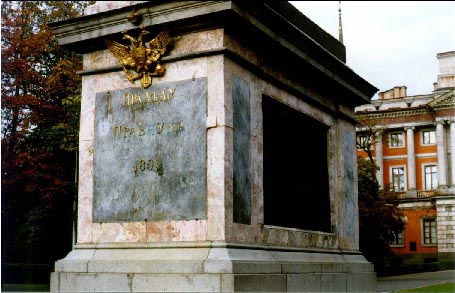

The comparison of structures of different granitic rocks. The drawing by D.Dolivo-Dobrovolsky. Rapakivi-granites; Karlahti granite from modern quarries in the vicinity of Priozersk (Railway Station Kuznechnoye); Gneissoid granite; Porphyry granite Vozrozhdeniye from the Karelian Isthmus. Serdobol Granite The rock quarried in the vicinity of the town of Serdobol (today’s Sortavala) is the oldest building, decorative, facing stone traditional for St.Petersburg used in sculpture as well. It was brought from a number of quarries located on the shore and islands of the northern part of Lake Ladoga. That stone was used as blocks and slabs in masonry foundations, for the construction of abutments of the first in the >city cast-iron Annunciation Bridge over the Neva(Bridge of Lieutenant Schmidt at present), for the making of pedestals to the monuments to Catherine II and Nickolas I. It was applied in facing of plinths of the house N 43 in Great Naval Street, Nicholas’ Palace and many other edifices. The whole height facing with Serdobol Granite of the former Wawelberg’s House is one of the example of such a kind. The columns with statues of Victory at the beginning of Horse Guards Boulevard, the columns of the portico of Nicholas’ Palace, the Jordanian Staircase of the Winter Palace, the Hall of Twenty Columns and the Main Staircase of the New Hermitage facing Millionnaya (Million) Street. Finally, the figures of Atlantes decorating the portico of the New Hermitage are carved of this granite. This list does not exhaust all the uses of Serdobol Granite use. Nowadays the rock is not employed. Everywhere in constructions and ornaments Serdobol Granite exhibits massive, homogeneous, fine-grained structure and even sober colour. However, in real situations different rocks and their varieties served as the material for building under the name “Serdobol Granite”. The most frequently employed type of rocks are grey gneissoid granites. Their fine-ganular groundmass consists of quartz, feldspars and small black flakes of biotite aligned parallel to one another. Somewhat larger inclusions of grey feldspar are strewn in this dark, or light-grey aggregate of minerals. Another variety of stone is a homogeneous, fine-grained dark-grey rock. A futher stone is a spotted and banded rock, the texture resulting from the presence of dark schistose inclusions enriched in biotite. There are massive, fine-grained bluish-grey granites and other varieties of stone as well. Almost all Serdobol Granites include thin feldspar layers, or veinlets that are correspondingly concordant with the banding, or cut it at various angles. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 1. Mineralogical composition (Vol.%), size of granularity and ultimate strength of granites at compression. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nystadt GranitesThis Finnish stone went into the building of St.Petersburg in rare instances. It was quarried near Nystadt (UUsikanpunki) town on the shore of the Gulf of Bothnia at the deposits Vezinari etc. and was used for the whole facade facing of the once-Russian Trading and Industrial Bank in Great Naval Street. The rock is medium-granular, or coarse-grained in places, massive, and consists of plagioclase, quartz and inclusions of biotite. The granites briefly outlined above, as well as rocks similar to them exhibit different strengths and durability. As it is obvious from Table 1, the most durable are Serdobol Granite and stones from Kovantsaari and Gangut. Rapakivi-granite shows the least resistance to compression and retains polish worst. All these granite rocks have a Precambrian (Proterozoic) geological age. 2. MarblesWhite statues of the Summer Garden, pink columns of the Marble Palace, floors and walls of St.Isaac’s Cathedral having different colours – just these come to mind when the word “marble” is mentioned.Italian white marbles The first rocks that embellished St.Petersburg as early as the time of Peter the Great’s reign were Italian white marbles: in 1717-1724, statues and stone busts by famous Venetian sculptors such as D.Bonazza, P.Baratta, A.Tarsia, D.Zorzoni, G.Gropelli and others were bought to adorn the Summer Garden. Carved of Carrara Statuary Marble are figures by Paulo Triscorn. They depict Dioscuri as young-athlete attempting to control rearing horses. The statues adorn the main facade of the Horse Guards Manege (Manege of the Household Mounted Regiment) in St.Isaac’s Square. Two guarding lions in front of the entrance of the former house of A.Ja.Lobanov-Rostovsky in Admiralty Prospekt are made of the same rock. Bluish-grey marble “Bardiglio” quarried at the deposits in the Serravezza district of Carrara environs is used in the facing of St.Isaac’s Cathedral. St.George’s Hall in the Winter Palace and the Pavilion Hall of the Small Hermitage are richly decorated with Sicilian marble. Unlike white statuary marbles, coloured ones occure very wide. Ruskeala Marbles Among native deposits of coloured marbles, the first were from the quarries of Ruskeala. These rocks have a proterozoic age. They are characterized by very variable composition and therefore they were used in various commissions. The dominant rocks of the deposit are dolomitized marbles containing two main minerals – calcite and dolomite. The rocks were applied for facing and interior decoration of buildings, St.Isaac’s Cathedral as an example. Marbles consisting of pure calcite served as a material for lime production. A system of joints existing in the marbles of the deposit made it possible to hew off blocks of marble weighing as much as 25-30 tons. The colouration of Ruskeala Marbles changes from snowy-white to dark-grey, almost black, and from light-yellow-green to dark green. The colour is determined by presence of graphite, radial green minerals – actinolite, grey-green chlorite and diopside, yellowish-green serpentine, grey quartz finely dispersed in a clcite. So, the colour of these marbles is not monotonous, the rock having variable banding which forms an original ornament. Unusual patterns of Ruskeala Marble result from banded texture with layers of different colours, from several millimetres to 2-2.5 m in thickness, and from thin veinlets. The bands are not infrequently plicated, fractured and swollen in places. Ruskeala Marbles were quite workable and could assume glossy polish, which made them very decorative. In accordance with their decorative properties, the rocks were classified into five groups, or “numbers”, the first three “numbers” being especially valued for their beauty. They were represented by grey-bluish rocks with grey and white bands, grey stone with a great quantity of radial green actinolite and banded grey-white marbles. The Minerals of Ruskeala Marbles possess different physical-chemical properties and, in consequence, are variously preserved. In particular, needle-shaped green actinolite (calcium-magnesium silicate) is considerably harder than calcite and dolomite and so it has been not nearly so rapidly weathered as the latters. It can be seen, for example, at marble slabs of portals and, especially of the floor of St.Isaac’s Cathedral. Nowadays, needle-crystals of the actinolite stand several millimetres above grains of the limes. Very harmful constituents of Ruskeala Marble are small crystals of golden pyrite. Under urban conditions, pyrite is subjected to oxidation and turns to brown iron ore (limonite), the process of change initiating a rapid disruption of the stone. Such was indeed the case already after several years St.Isaac’s Cathedrals’opening, some facing slabs of Ruskeala Marble had been broken up. The most fractured of them were replaced with insertions of Italian bluish-grey marble “Bardilio” during the restoration of the Cathedral in 1879-1898. Juvensky Marble Juvensky banded Marble of a Proterozoic age, second to Ruskeala one in its quality, is very beautiful. It was also quarried far into the past. The deposit was situated not far from Serdobol town located on the Juven (Joensuu) Island on Lake Ladoga. The distinguishing features of this marble are sharply defined black, or bluish-grey and white bands of width 5-10 cm. Together with Ruskeala and Tivdiya Marbles, the stone was used for facing of the Marble Palace and Engineers’ Castle. Tivdiya Marble The rock is frequently called Belogorsk, or Belaya Gora (White Mountain), and Olonetz Marble. It displays fine decorative properties: wide range of bright, deep colours, semi-transparency, diversity of patterns. It represents a typical dolomitic marble, that is, a rock composed predominantly of colourless dolomite. In addition to dolomite, Tivdiya Marble contains pale grains of quartz and less common calcite. Calcite in places is rather abundant, it forms veinlets usually white in colour. These veinlets are branching and cut one another, forming complicated patterns. Evident here and there in the central parts of the veinlets are small cavities or interstices, on the walls of which fine lustrous crystals of calcite, quartz and occasional hematite can be seen.

Columns of the portico of Apraksin's house were cut out of banded Juven Marble. The prevailing colour of Tivdiya Marble is pink, but dark red-brown, brick-red, light-red and cherry-red with white veinlet varieties occur as well. The pink and red colouration is caused by a finely dispersed admixture of hematite, otherwise present as dust-like red-brown inclusions in crystals of dolomite or concentrated on boundaries of grains of dolomite or quartz. Seven varieties of the marble were distinguished at the Belogorsk deposit. These groups of stone, like Ruskela Rocks, were assigned the “numbers”. Homogeneous light-pink marble was more favoured, next were dark red-brown and red rocks, as well as pink stone with dark-red veinlets and spots. It was precisely those varieties of marble that were quarried as monoliths to a length of 7-8 m. Columns, pilasters and interior decorations of the Marble Palace, Engineers’ Castle, St.Isaac’s Cathedral, window-sills in the Winter Palace had been made of those kinds of marble. Belogorsk Marbles are of greater hardness due to the considerable (up to 15%) content of quartz. Therefore these stones fall in to a category of the least workable rocks in accordance with the degree of difficulty of their sawing, polishing and glossing. Sawing of the marble blocks was performed with the use of machine-tools intended for processing of granites. Nevertheless Belogorsk Marble can take polish very well, though in this case its surface displays a “shagreen”, character, on account of hardness variation from dolomite to quartz. Twenty more kinds of Olonetz Marbles had been found and were developed not far from the Belaya Gora deposit, on the shores of lakes Krivozero, Lizhmozero, Sundozero, etc. On the whole, these rocks resemble the Belogorsk varieties in colour, pattern and other properties.

Pink (of different patterns and hues) Tivdia Marble was used as bright insets and additions to general decoration of buildings and monuments. The picture shows the rock in the pedestal of the monument to Peter I standing in front of the Mikhailovsky Castle. Uralian Marbles Decorative coloured marbles from deposits of the eastern hillside of the Middle Urals were also brought for St.Peterburg’s building. The wide marble belt stretches south to north from Gorny Shchit (Mountain Shield) village to the Gumeshevsky mine. White marble with grey bands and spots, a grey one with black and yellow veinlets, yellowish-grey rock with indistinct spots and bands were quarried in the stone pits of the deposits Polevskoye, Gorny Shchit, Mramorskoye mill, etc. All of them are assigned to calcite marble in their mineralogical composition, their different colouration being determined by the presence of admixed carbonaceous matter and hydrous ferric oxides. The distinctive features of the Uralian marbles are the coarse-grained texture and a measure of tranlucency to some depth. The rocks were hewn off as large blocks which permitted the use of them for making of architectural details of any size. Besides coloured marble, white one tinged with warm yellowish occured in the Urals as well. Sometimes Russian sculptors appreciated that coarse-grained rock to be superior to Carrarian “Statuario”. One can see the Uralian marbles at interiors of the Marble Palace. The most bright, judged to be semi-precious, coloured marbles were brought by sea directly to building sites of the Marble Palace and St.Isaac’s Cathedral. The green, red and yellow rocks were imported from Italy, red ones – from France and so on. They were used for decoration of the most important parts of interiors. Levanto Marbles (Serpentinites) Green Levanto Marble that is in fact serpentinite was quarried to the north-west of Carrara, at Levanto town - hence the name of the marble: Verde di Levanto. It contains abundant green and dark-green serpentine, scarred by thin branching veinlets of snowy-white calcite. The marble was extensively used in architecture. It closely resembles green antique marble Verde Antico quarried in stone pits situated at the town Larissa in Greece and abandoned as far back as antique time (only in 1886 they were newly rediscovered). Every so often, art-critics, trying to determine types of green serpetine bearing marbles, muddle them together and take one for another. One of the varieties of Levantian marble is dark-red rock Rosso di Levanto, serpentine of which has dark-red colour due to admixture of fine-crystalline hematite. There patches of dark-green mineral - bastite and numerous veinlets of white calcite in the rock. Both the varieties of Levanto marble contain considerable quantities of the very soft light-green mineral - talc, and therefore these rocks are rather unstable. Siena Yellow Marble Deposits of beautiful yellow Siena marble were located in Tuscan, 60 km to the south of Florence, in the vicinity of Siena. The colouration of different kinds of the marble changes from straw-coloured and pale-yellow to deep, intensive golden-yellow. Thin, often zigzag, white, black, reddish sparse veinlets and patches stand out against this background. The marble possesses highly [very] fine-grained structure and is almost completely opaque. “Griotto” marble One of the most splendid marbles is red Griotto quarried in France, at the northeastern off shoots of the Pyrenees, near Narbonne. Many Griotto marbles came to European cities from the Meix Valley to Belginm. The rock is a homogeneous calcite marble coloured dark cherry-red and, in places, bright-red with finest, dust-like admixtures of hematite. Snowy-white rounded spots of calcite representing the remains of badly preserved fossilized shells of brachiopods make the rock very elegant. 3. Sedimentary carbonate rocksOf this group of rocks, limestones, dolomites, dolomitic limestones and limy dolomites were used in the building and stone decoration of St.Petersburg. The belt of distribution of limestones, dolomitic limestones and dolomites stretches submeridianally, 20-25 km to the south of the Neva and Gulf of Finland. The south-western part of the belt near the settlements Elizavetino (Elisabeth’s), Kikerino, etc. consists exclusively of dolomite. Quarries of limestone were located along the Pudost river in the area of Gatchina. From that river the name of the rock Pudost or Pudozh Stone had come.Pudost Limestone This yellowish limestone termed also travertine or tufa, was produced by the precipitation of calcite from water springs when older calcareous rocks had been dissolved. There were two varieties of the stone: highly porous “ornamental” tufa that found its major use in facing and lining of garden grottoes, or for construction of artificial rocks and similar park adornments; and dense, massive tuff such as one applied for the facing of the facades of the Kazansky Cathedral. The typical property of Pudost limestone was as follows: as long as the stone remained in the ground, it could be cut with a knife and sawn with an ordinary saw, but in the open air, the rock hardened and its strength increased in the course of the time. Therefore Pudost Limestone was quite workable at first and later its durability compared well with marble’s strength. Built of blocks of this tufa are columns of Kazansky Cathedral. A number of sculptures are carved from the stone, “Nymphs carrying the Celestrial and Earthy Spheres” set up on both sides of the main arch of the Admiralty among them. Pudost quarries of the tufa were worked out a long time ago. Not far from them – at the village Paritsa, a deposit of dolomitic limestone was found. That stone, rather than Pudost (reference to which can be met in many works), was used for building of the Gatchina Palace, Putilovo Slab Limestone The best building limestones occur in the eastern part of the belt of carbonate rocks, between the Naziya and Lava rivers. Among them is the most notable “Putilovo Slab” that was widely used in the construction of St.Petersburg and mentioned in this book repeatedly. As noted above, plinths of many edifices and bases of monuments of our city had been carried out in Putilovo Slab. It was copiously used for making steps and cornices, streets were paved with that limestone. Even 30-35 years ago those yellow-ish-white slabs could be seen in the rows, or lines and prospekts of Vasilyevsky Island and over other areas of the city. After the streets had been asphalted, the slabs were transported to the shore of the Gulf of Finland - to the Gavan (Harbor), where they are now lying. Putilovo Slab represents Ordovician limestone that is dolomitized and argillaceous here and there. It contains more or less abundant inclusions of green mineral glauconite – a silicate of very complex composition. There is semi-transparent quartz in some places of the rock. Especially large quantities of quartz are characteristic of the slabs from the Tosna river. Fossil molluscs - cephalopods and sea-urchins are common in the rock. This limestone occurs as a bench of bands from 0.5 to 2 m , rarely to 4-10 m. Usually clay partings lie between the limestone bands. Depending on thickness of bands, their density, jointing and other properties, the whole of the series of the glauconitic limestones was divided into 12 kinds of varieties. The best of them called “Bratenik” and “Staritsky” are grey tinged with green. As a rule, they do not contain yellowish partings and patches of argillaceous matter which would diminish the quality of the slab. Those varieties characterized by excellent mechanical properies and high strength under compression (85-110 MPa) were predominantly used for construction of steps and plinthes. The poorest kinds of the limestone : “Green”, “Soft”, “White-eye”, “Velvet” went into rubble, or quarry stone. Putilovo Limestone is broken both lengthwise and crosswise. Such a jointing formed separate blocks earlier called “basmas”. Stone-cutters used that natural jointing, hewing slabs off. Only crow-bars, pickaxes or mattocks and rarely shot powder were employed in the process. However the existence of joints not only contributed to quarrying of Putilovo Stone, but also prevented the obtaining of large blocks. In addition, that limestone was prone to weathering and displayed caverns and layering. Therefore, in spite of its fine appearance, particularly when polished, Putilovo Limestone has not found wide application as decorative material. Nevertheless it occurs rather often in facing of socles of buildings erected in the old quarters of St.Peterburg. Kirno Stone Ordovician light-grey with lilac spots limestone transformed by natural metamorphic processes, was brought to Petersburg from the Eastland province of old Russia beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. Its quarries were situated 40 km to the south of Revel (Tallinn), near the grange of Kirna that gave the name to the rock. Similar to Pudost Stone, Kirna Limestone is soft when underground and hardens in the air. Except for dominant calcite, the rock contains quartz and dolomite. The resistance to compression of Kirnovsky Limestone is above the value for Carrara Marble and even greater than the strength of Serdobol Granite. Quarrying or mining of the limestone usually began in spring and was accomplished by the 1-st of September, or even earlier in order that the quarried stone would dry out and not break at the onset of frost. It took polish well and therefore was used for carving of elegant architectural details. For instance, capitals, columns, vases on the facade of the New Hermitage, as well as the plinth of the portico were cut from that stone. In quarries it occurs as rather thick layers that permitted to hew off large rectangular blocks weighing as much as 15-16 tons. Revel, Ezel and Wasalemma Marbled limestones These ordovician rocks imported to St.Petersburg from deposits of Eastland province are slightly metamorphosed limestones and dolomites. During metamorphism their textures became more coarse-grained, which made the stone have the proporties of some marbles. At the end of the XVIII-th century, 110 vases were put up above the attic of the Marble Palace. They were carved out of white metamorphosed dolomitic limestone quarried at Mount Laksberg near Revel. Similar marble was also mined on the Ezel Island (today’s Saarema Island) in the Baltic Sea. Wasalemma marbled Dolomite occures in the area Kloostri-Wasalemma, North Estonia and represents a coarse-grained dolomitic rock. Its colour is either white, or yellowish and light-grey, or even pink. Once polished, the pink stone became brighter, its colouration intensified and the price rose. Made of Wasalemma marbled Dolomite are complex architectural details and adornments of the facade of the house N 14 in Malaya Morskaya (Little Naval) Street. A great deal of similar stone was used for making steps, balustrades and pavement slabs. Estonian marbles and dolomites are valued for their properties and are worked up to the present time. 4. Sandstones and quartzitesSandstonesOnly imported sandstones – German or Polish ones – were used in the course of the building of St.Petersburg. Early in the 1850-s light-grey Bremen Sandstone appeared in the city for the first time. It consists of fine well rounded grains of quartz cemented with silica. The stone is very strong, resistant and so was applied on different purposes. For example, made of Bremen Sandstone was the main entrance and balcony of the former Palace of Grand Duke Vladimir Aleksandrovich on the Palace Embankment. The same stone was used for facing of the facade of Yusupova’s Mansion in Liteyny Prospekt. It went into carving of sculptures, columns and different ornaments. The disadvantage of Bremen Sandstone is that its originally light-grey colouration becomes dirty-grey, as a rough surface of the stone absorbs dust and soot rather intensively. Deposits of this sandstone occur 100 km to the south of Bremen in the Teutoburger Wald and Vezer Mountains. They have been exploited for almost 300 years. In general, quarrying of various sandstones in German duchies was carried out extensively. Especially famous were sandstones of different colours from Baden and Württemberg. They consist of quartz with insignificant amounts of mica, the cement being represented by silicified argillaceous matter. Usually the sandstone is light-grey, but there are red and yellow varieties as well. The former is coloured with dusty admixture of hematite, the latter – with brown hydrous ferric oxides. When the cement contains green chlorite, the colour of sandstones becomes green. Quarries of the sandstones occur over the whole Schwazzwald and along valleys of the Neckar, Alb and Kintzig rivers. Württemberg red, yellow, green sandstones were used, for example, in revetment of the facade of the once Russian Bank of Foreign Trade built in Great Naval Street, red Baden Sandstone can be seen in facing of the ground floor of the house N 8 on the Admiralty Embankment.

Polish sandstone used for the facing of the Russian National Librery buildings (Ostrovsky sq., N 3). Late in the 1880-s, sandstones from Poland came into use in St.Petersburg. They were quarried in the Radom Province. One can recognize Polish grey and yellowish-grey sandstones in the facing of the house at N 10 in Great Naval Street and in the upper part of the facade of the house N 1 on Nevsky Prospekt. The example of use of red sandstone is the facade of the building at N 4 in Gorokhovaya (Pea) street. Those sandstones were also called Shidlovets and Kunov after the names of the corresponding quarries. Shidlovets Sandstone was applied not only as facing stone, but for production of wheels for grinding and polishing of marble as well. Quartzites Brusna and Shoksha Proterozoic quartzites were used in St.Petersbur g. Brusna Stone was quarried on Brusna Island hear the southwestern shore of Lake Onega where the thickness of its layers amounted to as much as 6 m. It represents a dense massive, slightly schistose grey-green rock, or dark-green one in places. Being rather inconspicuous in the colour and heterogeneous in the structure, Brusna Quartzite characterized by the high resistance to mechanical attacks was almost exclusively used for paving. Made of this quartzite, are the steps in the Winter and Marble Palaces, as well as the Solium in the Kazansky Cathedral.

Crimson Shoksha Quartzite in the pedestal of the monument to Nicholas I. Shocksha Quartzite is one of the most familiar stones of the North-West of Russia. It was also called Shokhan Porphyry, or “rouge antique”. The Shoksha deposit known for more than 200 years is located on the western shore of Lake Onega, 60 km to the south of Petrozavodsk city. The quartzite makes up a lens-body 15 m thick that grades into yellowish-grey and grey sandstones. Shoksha Quartzite is a very dense homogeneous fine-grained rock consisting of rounded, or subangular particles of quartz of size 0.1-0.2 mm, covered with thin red-brown films of hydrous ferric oxides and anhydrous oxides of iron. The grains are cemented with secondary quartz, as the last mineral. The rock shows constant crimson, or dark-red colouration and high strength. It is extremely difficult-to-machine though polishable. Hence the stone is considered to be a valuable decorative and facing material. Shoksha Quartzite, excellently holding its polish arrests our attention in the frieze of the Engineers’ Castle, plinths, cornices and some other details of the interior of St.Isaac’s Cathedral, as well as in the pedestal of the monument to Nicholas I standing in St.Isaac’s Square. The hardness and chemical stability of the quartzite provides a longevity of all architectural elements and decorative ornaments made of the stone. Sometimes red Shoksha Quartzite is used for paving. Talking of the fame of the Karelian red porphyritic stone, it is worth making mention of the fact that in 1847, the French government addressed a request to Nicholas I to sell Shokhansky Porphyry for the tomb of Napoleon. The tsar had ordered to present France with 27 specially quarried monoliths, the biggest of them being 4.6 x 2.19 x 1.06 m3. The sarcophagus set up in the Parisian Dome des Invalides was constructed of those blocks. 5. Diabases, gabbros and porphyriesDiabasesThose rocks were highly valued in the old St.Petersburg as a material for tombs and cemetery monuments. The most prized stone was black Swedish diabase that was mistakenly termed black Swedish granite. The nearest to St.Petersburg Ropruchey (Rop Brook) deposit of diabase is located 35 km to the south of Petrozavodsk city, on the shore of Lake Onega, close to Rybreka (Fish River) settlement. The development of the deposit got under way after 1924. Deeply black Ropruchey Diabase splits into uniform in size smooth plates and readily lends itself to polishing. Diabase was often used as flagstone. By that time diabasic pavements had received wide acceptance in Europe, and Russia kept pace with the fashion. Streets and roads in St.Petersburg were paved with small bars of diabas having regular shape and equal size. In such a way Blagoveshenskaya (Annunciation) Square (later Truda, that is Labour Square) was paved. The pentre douce of the Central State Historical Archives housing the buildings of the Senate and Synod in Decabristov (Decembrist’s) Square is too paved with diabasic bars. Diabasic pavement demonstrates the durability, as the limits of the compressive strength of the rock is 220 MPa. However a pavement of such a kind has important shortcomings: first, it is rather slippery, particularly in damp weather. That is why presently diabase is used for pavement only in rare cases. So, in 1977, by the 60-th anniversary of the October Revolution, asphalt covering the Palace Square was replaced by diabasic bars, parts of the pavement being separated by lengthwise and transverse stripes of pink-red porphyritic granite. Gabbro This stone is used very rarely in St.Petersburg renowned for its commonly grey sky and bad climate. The dark-grey colour of gabbro turns deep-black after polishing. Details of spotted structure of black gabbro are clearly visible on glassy polished surfaces of slabs facing the ground floor of the house N 35 in Great Naval street. The rock is composed of fine black crystals of pyroxene and lighter grains of grey feldspar - plagioclase. Seen here and there in the stone are sparkling submetallic lustre grains of the black magnetite that is an essential constituent of gabbro. One of the most beautiful varieties of gabbro is labradorite. Columns of the building of the former Head-office of Light Industry lining Voznesensky (Ascension) Prospekt for the whole block between Sadovaya (Garden) Street and Fontanka River embankment were faced with labradorite. Large boulders of the rock transported by an ancient glacier from Scandinavia were found sometimes in the environs of St.Petersburg. In modern times decorative labradorite is quarried at the deposit located near Zhitomir city, the Ukraine. Porphyries Rocks that bear no resemblance to one another in their appearance, colour, texture and mineralogical composition are called “porphyries” in old works on the history and architecture of St.Petersburg. For instance, pink granite-porphyry obtained at a quarry developed in the vicinity of Elfdahlen in Sweden is noted in the descriptions of the vase set up in the Summer Garden. The pedestal of the vase had been cut of dark-red feldspathic porphyry that is known as Antique, or Egyptian porphyry. The rock displays the characteristic colour and pattern, or structure: fine rectangular crystals of light-pink, or white feldspar stand out sharply against dark-red, red-brown, or cherry background. Two huge black vases standing at Petrovskaya (Peter’s) landing-place on the Neva were often said to be hewn out of porphyry. To our mind, the rock resembles a coarse-grained gabbro, but this can not be proved without more data. 6. Rare kinds of stoneThe capital of the Russian Empire was growing simultaneously with the development of the national mining industry. As deposits of stones of new types came to be found, their production was brought to St.Petersburg for its building and decoration. Among the most valuable, costly and rare stones were malachite and lazurite. They were used only for decoration of interiors of the richest and most magnificent edifices. In addition, here and there in the central streets of St.Petersburg dark, almost black stones can be met. They are classified as slates and Solomino Breccia.Malachite The world-renowned Russian decorative stone malachite derives its name from the Grecian word that sounds as “malyahke” and means “rose-mallow, or “hollyhock”, because the colour and lobed shape of leaves of the plant resembles the colour and pattern of the mineral. Malachite was known in Ancient Greece, when the famous temple of Diana in Ephessos was decorated with it. Pliny wrote that malachite was imported from Arabia. In pre-Petrian Russia the same mineral was called “a guide to copper” as copper ores were usually accompanied by a green powdery coating of malachite. Green patina covering old coppery roofs, copper and bronze statues contains malachite along with sulphates and chlorides of copper. Chemically malachite represents a carbonate of copper. Its earthy powdery variety sometimes called Olympic green (Green copper) is most frequent. Only nodular kidney-shaped aggregates of malachite consisting of thinnest, fine radially arranged needles are valued as semiprecious or jewelry stones. The best large nodules of malachite are coloured dark-green, almost black at the exterior and are highly lustrous. They are called “green glassy head”. In cross-section such nodules display beautiful clear concentric zonal patterns formed by alternating lines of different hues of green. Both dark-green and light-green are encountered, light-green and slightly blueish varieties being considered to be of particular value. Blueish malachite was called “Turquoise”, or “Curly”. The last name is connected with the following peculiarity of the “Turquoise” malachite: It usually occurs as rather small nodules (kidneys) with diameters of 3-5 cm and less. Such a stone looks curly indeed. Its dense, solid kidney-like aggregates are polishable, but as with all carbonates, they dissolve gradually in water containing carbon dioxide and therefore their polish grows dull and needs renovation. History of the development of malachitic deposits in Russia is rather full. At first, malachite was found in foothills of the Urals in 1635. In the beginning it was used as copper ore. Discovered in 1702 was the Gumeshevsky deposit copper of which seemed to have been mined even at the end of the first millennium B.C. Somewhat later they found malachite there as well. The stone was suited for artistic wares. Exploitation of the Gumeshevsky deposit started in 1728 and went on up to 1874. The Gumeshevsky mine was sited 55 km to the south-west of Ekaterinburg (Catherinesburg) – at the former Polevskoye mining enterprise. That was precisely the deposit where a wonderful block of malachite weighing as much as 1504 kg was discovered. Turchaninov -an owner of the mine, had sent the block to Catherine II who, in her turn, presentedthe Museum of the Mining Institute with the stone, where it is now exhibited. At that time the block cost 25. 714 roubles and 28 copecks. Malachite was also mined as part of the copper deposits of the Middle Urals, in the vicinity of Nizhny (Lower) Tagil. The most notable of them was the Mednorudyansk (Copper ore) deposit. Jewelry malachite occuring there, as well as similar varieties from other known deposits, originating from the process of oxidation of copper ore. Underground waters mineralized with sulphate of copper dissolved nearby marble terranes, forming karst scours and caves. Interaction of copper sulphate solutions with calcite and waters saturated with carbon dioxide gave rise to globulites of malachite. Those globulites settled inside the karst scours and began to grow, transforming into kidney-like aggregates. It should be noted that, as a rule, additional secondary minerals of copper arise together with malachite. Therefore very fine rounded segregations of dark-green copper phosphate - ehlite, or pseudomalachite, and blue copper silicate – chrysocolla often occur in malachite, especially in its lightest parts presenting the mentioned above “turquoise” kind of the stone. Unconsolidated earthy masses of malachite served as a material for the production of green pigments. Such a variety of malachite from the Gumeshevsky mine was used for painting the roof of the Winter Palace in 1785. At the same time they started to make jewelry of malachite and since the 1820-s, the stone became fashionable. It would be mounted in gold and adorned with diamonds. A short time later the output of malachite increased so much that it became considered to be industrial and even facing stone rather than just for jewelry. In 1836 a malachitic block with a volume of 5.3 x 2.5 x 1.8 m3was found at the Mednorudnyask deposit. The mass of the block exceeded 260 tons and the rock was of the highest quality (at that time the price of malachite was 50-60 roubles for a kilogram). The decision was made to use it for decoration of interiors of the Winter and Anichkov Palaces, as well as of the main cathedral of St.Petersburg – St.Isaac’s. Columns, vases, table tops and other unique articles came to be machined from malachite. It is impossible to cut large monolithic lengths of malachite as even the largest nodules of the stone usually are no greater than a human fist size and are often divided with interstices and cavities. Thus all columns and other remarkable decorations were executed by the technique of “Russian mosaic”. In spite of the name, that approach had come to Russia from stone cutters’ workshops of Florence where it was employed in production of decorative articles of costly and rare stones as early as the XVI-th century. It was precisely to the workshops of Florence that the owners of the largest deposits of Russian malachite Demidovs sent the magnificent stone. And thence malachite items spreaded over all European countries. At a later time the Florencian mosaic technique was adopted by Russian stonecutters from the diamond-mills of Peterhof and Ekaterinburg who made considerable advances in their works. That type of mosaic possibly attained the name “Russian msaic” as late as the XX-th century. The technique of “Russian mosaic” consisted in the following procedures. First and foremost nodules and pieces of malachite were sawn into parallel plates 3.5-4 mm thick. Thereupon, after their fitting together in colour and pattern, the plates were glued on a slate or cast-iron base. Malachitic powder was added to the glue to make joints between the fragments invisible. A master’s skill resided in such careful fitting of malachitic plates that the stone surfaces, being polished and glassed gave the impression of malachitic monolith having a certain pattern that could be fluidal, orbicular, and so on. Huge malachitic vases, tops of tables, doors created by Russian stonecutters for the First World Exhibition in London in 1851 made an indelible impression. Visitors to the exhibition could not believe those things had been made of the material which they had been accustomed to consider as a precious stone. After 1850 the output of the Uralian malachite began to decrease sharply and by 1870 the mining had been almost entirely stopped. The mines became deserted, were blocked up and flooded. Yet some scientists argue that considerable masses of malachite are left intact. In modern time, a bare minimum of industrial malachite is mined at several copper deposits of the former USSR. Unfortunately the stone of the beauty of the Gumeshevsky or Mednorudnyansk malachite has not been discovered up to the present. Nowadays, plenty of malachite comes on the world market from Zaire. However it ranks below the famous Uralian stone in the decorative quality. Lazurite Lazurite almost is not applied for facing of buildings as its price was always considered to be superior to malachite. Nevertheless lazurite has long been in use. Made of that beautiful blue stone were seals, amulets, ornamentation, statuettes, expensive blue paints, or pigments in Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Middle Asia. At that time the stone was variously called: “safir”, “lazurine stone”, “lazuric”, “lapis-lazuli”. In Russia it was also known as Armenia, or Bukharia Stone in connection with its import from Afghanistan being conducted by Armenian and Bukharan merchants. The modern term “lazurite” made its appearance in the XVIII-th century. Lazurite represents a silicate class mineral coloured blue ranging from light-blue to dark-violet. Bright-blue lazurite is particularly valued; too light, greenish-blue and deeply dark-blue varieties are considered to be less expensive. Lazurite is polishable and holds polishing for a long time. Crystals of the mineral are perfect in shape, but few and far between. More frequently lazurite forms dense granular masses. As jewelry, so industrial lazurite presents polymineral fine-grained aggregate, that is lazurutic rock designated also as lapis-lazuli. Aside from lazurite itself, the rock contains white, or light-grey calcite, dolomite, mica and some other minerals. Most commonly, the lazurite content of rocks is not high. The size of its grains varies between hundredth and tenth parts of a millimetre, ranging to a few millimetres across in solitary instances. In places, deeply blue lazuritic grains stand out sharply against a light background. However lapis-lazuli of the best kinds contains scarcely any small white spots of carbonates or other minerals. Such a rock can be very embellished by fine inclusions of golden pyrite crystals sparkling against deep-blue background like small stars. The most remarkable deposit of lazurite known for about 5-6 thousand years is situated in almost impassable mountains of Eastern Hindukush, Badakhshan Province of Afghanistan. This deposit is called Sary-Sang, and lazurite mined here is spoken of as Badakhshanian. As a rule, Badakhshan Lapis-lazuli consists of massive extremely fine-grained lazurite and occurs as lenses and pockets in dolomitic marbles. The average size of the pockets is 30 x 50 x 10 cm Lazurite in Russia was firstly discovered in the Baikalian area by the outstanding researcher of the Siberia, academician E.Laksman in 1784-1785. Evidently then some quantity of that stone had been brought to St.Petersburg for decoration of halls of the Marble Palace, though the regular production of azure, or sky-blue stone started only in the 1850-s, after G.Permikin discovered seven deposits of it on the Slyudyanka (Micaceous) and Malaya Bystraya (Small Rapid) rivers in 1851-1852. The best samples of Baikal Lazurite compare well with the Badakhshan Rock in colour. Its bright-blue colouration transforms to blue-violet and redish-violet tints when the stone contains pink-red zeolites or lilic-blue variety of scapolite. Baikal Lazurite is distinguished from Badakhshan Rock by its more coarse-grained texture and considerably less quantity of pyrite. Solid masses of lazurite in the Baikalian area are rather rare. They occur as small pockets and have more often than not maculose, or spotted appearance. In 1857-1858 about 16 tons of Baikal Lazurite were transported to St.Petersburg. Its price was 62.5 roubles in silver for a kilogram. Since that time the diamond-mill of Peterhof began to produce mosaics, vases and other articles of Russian lazurite. In doing so, large objects were produced only by means of “Russian mosaic”. The technique therewith was more simple than in the cases of use of malachite, as lazuritic rock has no any special pattern. Just in such a manner the two columns of the icnostasis in St.Isaac’s cathedral had been created of the precious Badakhshan Lazurite. Slate Black schungitic slate is designated as simply slate, or aspidite. Deposits occur in Karelia. The best known of them is located at Lake Nigozero 2 km to the north-east of Kondopoga town, on the western shore of Lake Onega. It has been worked since the XVIII-th century. In 1819 K.I.Arsenjev - a member of the Russian Mineralogical Society, reported: ”There is so much roofing slate at this ourcrop that it seems to me the whole Russia could be supplied with slates from here. The slate is found in two varieties. One of them consists of blocks and exhibits poorly defined bedding. The second is thin-platy, with distinct lamination. The last rock splits forming plates of size 50 x 50 cm2, rarely larger. Their colour is deep black and thickness ranges from 2-10 cm to 15 cm. Slate is hardly polishable, therefore its lustre usually is dull. The inner socle of St.Isaac’s Cathedral is lined with plates of slate.

Slate on the roof of the Burial Place for Grand Dukes in the Peter and Paul Fortress. The photo has been taken by H.Walendowski. Solomino Breccia This very unusual stone can be observed in St.Petersburg only in St.Isaac’s Cathedral where plaques, or panels and round convex medallions arranged on the walls and appearing rather picturesque in the frames of pink Belogorsk Marble are made of it. The stone of panels and medallions seems to be uniform black, but actually it represents highly heterogeneous breccia consisting of angular pieces of dark-grey and light-grey fine-grained rocks contained in the matrix of black and dark-green serpentine. On occasion fragments of white quartz and calcite are recognized here as well. The breccia is excellently polished and its fine-grained fragments have high, almost metallic lustre while the groundmass of serpentine is rather dull. For the decoration of St.Isaac’s Cathedral, a block of the stone was specially quarried in the village Solomino (Straw) standing on the shore of Lake Onega in the vicinity of Petrozavodsk. “Solomino Stone” refers to a rock of a fairly compound composition: fragments of clay shale and quartz, as well as, in places, of very fine-grained black augitic porphyries and diabases are found in a matrix consisting of dolomite and serpentine. Earlier the rock was spoken of as marble, though its hardness and fragility (brittleness) were always noted to be considerably higher than those properties of marble. Solomino Breccia occurs as a rather extended rocky ridge. The quarrying and processing of that stone were carried out with great difficulties because of its fragility. Large blocks of the rock sometimes exceeding 1.5 m in length seemed to be monolithic, having no defects, but in the processes of the finishing – glossing and polishing – pieces of different size, broke off. Thus thoroughly polished, shining plates of Solominso Breccia in St.Isaac’s Cathedral are the result of the mastery, skill and patience of Russian stone-cutters. 7. Soap-stoneSoap- (or pot-) stone represents soft Proterozoic basic slates from the deposit Nunnalahti situated on the western shore of the big Lake Pielinen in Estern Finland. They consist ot talc (40-50%), magnesite MgCO3(40-50%), chlorite (5-8%), dolomite, calcite, ets. It is conceivable that the identical slates were imported from Sweden. The colour of the stone is very spectacular and varies from yellow and brown-ish-yellow to grey, greenish grey. The soft stone is a highly workable material for a sculptor’s chisel. It was one of the most popular rocks used in the Petersburg architecture of the Modern style lately in the XIX-th centuries. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To the beginning |